After my brief meltdown upon exiting the TED stage (and many encouraging words from those that happened to be trapped backstage with me while it happened), I headed out to meet what I had imagined to be an onslaught of excited people who had just seen my talk… and had tons of money to eagerly throw at me.

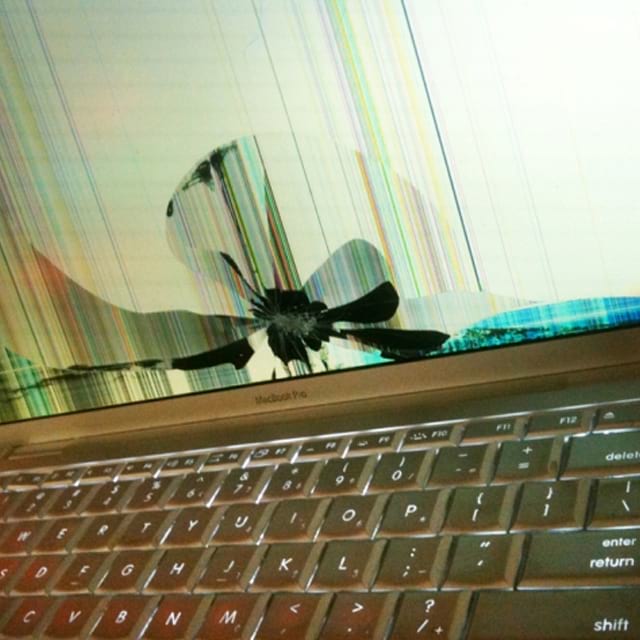

“Why didn’t you tell me sooner?” Jacob asked upon finding out that the Orbitar was not working at the TED dress rehearsal just one day prior to the talk. Knowing that “I’m an idiot” was a truthful yet unhelpful answer (that wasn’t going to boost my already low morale), I resorted to “I don’t know”, and we set off that morning in a scramble. Natan, Jacob and I, a ragtag trio of artists/hackers, depleted of money, resources, and sleep, and having no clue if the thing I was giving a TED talk about was even going to work.

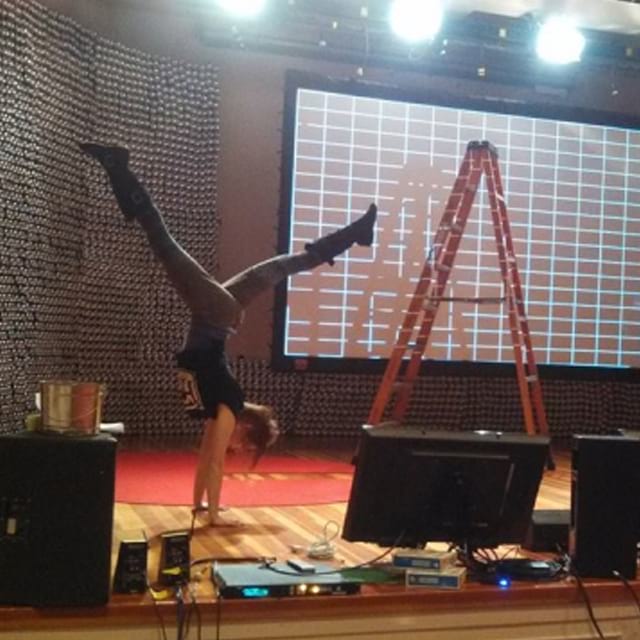

Despite my constant pestering of the TED folks, it seemed my one chance to test out, well, everything, was at 3:00pm the day before my talk. So there I was, a ball of nerves amidst the complete chaos that is TEDxBeacon Street less than 24 hours before the event.

The pieces were all falling into place. The speech was written (and re-written. and re-written again). The Orbitar glove cables had a freshly sharpied black coat. Jordan, the Max MSP musical guru, had arrived from Texas to help flesh out the TED performance. We were experimenting. We were rehearsing. We were staring at computer screens, a lot. We were... Orbitar-ing.

So there we were, the 2013 TEDxBeacon Street speakers, sitting in our swivel-y chairs around a long table for our first speaker orientation. It was no big deal, you know; a mechanical engineer, a Pulitzer Prize winner, an MIT professor, and... me... some sort of artistic/musical/entrepreneurial conglomeration with no particularly notable title.